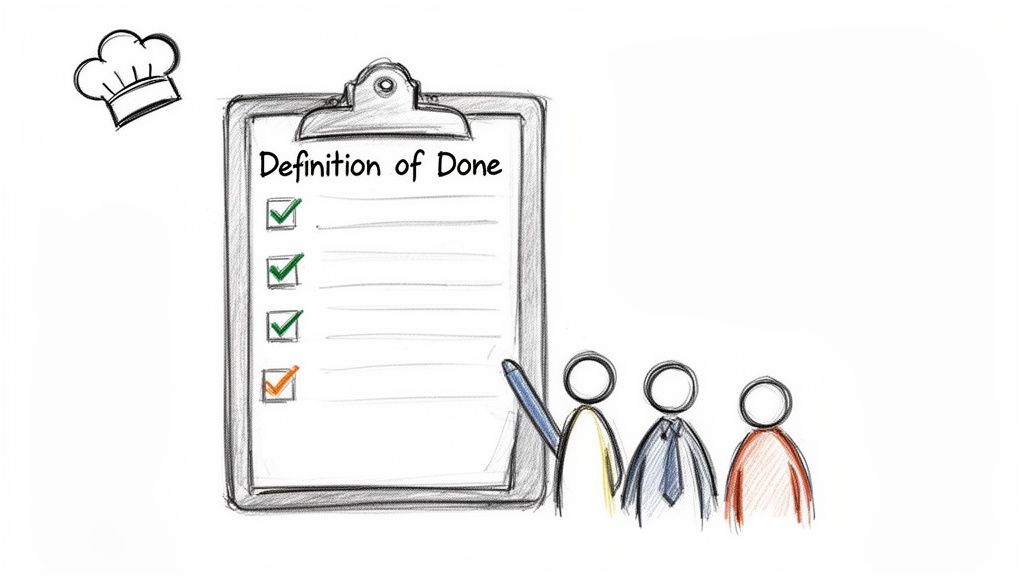

Think of it this way: a master chef would never let a dish leave the kitchen without a final quality check. Is it plated correctly? Is the temperature perfect? Does it meet the restaurant's high standards? The Agile Definition of Done (DoD) is that same critical quality checklist, but for your team’s work.

It's a straightforward, shared agreement that spells out exactly what criteria a task must meet before anyone can call it "complete."

So, What's Really in a Definition of Done?

At its core, the DoD is the antidote to the classic project killer: the dreaded "it's done, but..." conversation. It's what takes your team from a vague, subjective sense of completion to a concrete, objective standard that everyone understands and agrees on.

Without a solid DoD, one developer’s “done” might just mean the code is written. For another, it might mean the code is written, tested, documented, and reviewed. That kind of misalignment is a recipe for disaster, leading to painful rework, blown deadlines, and a whole lot of team friction.

A well-crafted DoD serves as a formal handshake between the development team and the product owner. It’s a promise that every single piece of work delivered at the end of a sprint has hit a consistent, agreed-upon level of quality. This isn't just about ticking boxes on a list; it’s about building a culture of transparency, trust, and predictability.

The best DoD is a team effort. Everyone (developers, testers, designers, the product owner) should build it together. This collaboration creates shared ownership and ensures the whole team is bought in before a sprint even kicks off.

When teams get this right, the impact is huge. We've seen teams cut their development cycles by 25-30% simply by implementing a clear, universal standard for "done." You can dig deeper into these agile insights and their impact on efficiency to see how small changes yield big results.

The True Meaning of "Done"

A great Definition of Done isn't a static set of rules dictated from on high. It’s a living document, built and maintained by the very people doing the work. It’s the team's collective commitment to quality.

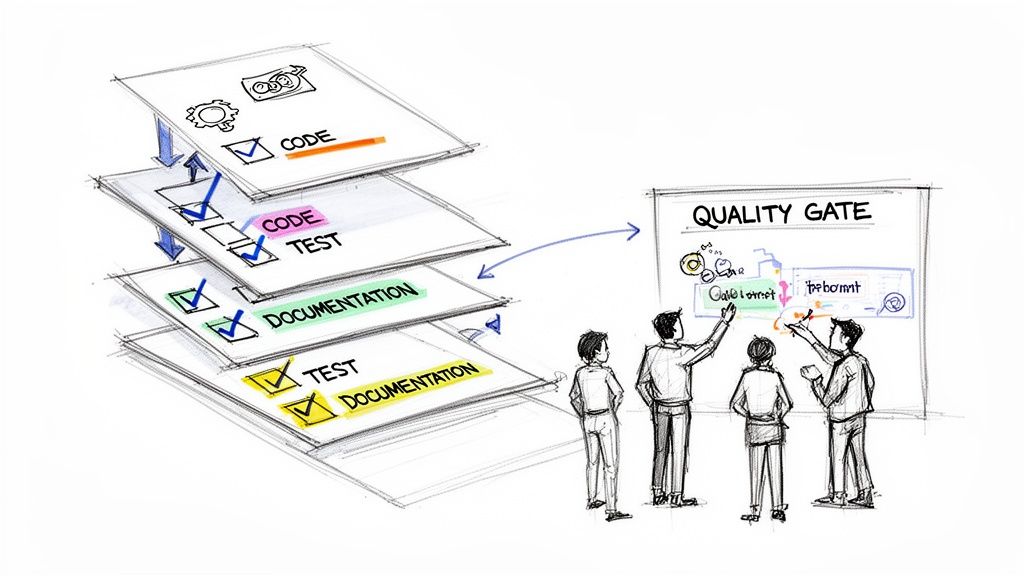

This checklist should cover all the steps needed to create a potentially shippable piece of value. What does that usually include?

- Code Quality: Has the code been peer-reviewed? Does it follow our team's styling and best practice guides?

- Testing: Are all unit and integration tests written, and are they all passing? Is our code coverage target met?

- Documentation: Have we updated any necessary user guides, API docs, or internal wikis?

- Deployment: Is the code successfully merged into the main branch without breaking anything? Has it been deployed to a staging environment?

This simple alignment ensures that "done" means exactly the same thing to everyone on the team, every single time. It’s the secret sauce for high-performing agile teams, eliminating ambiguity and killing last-minute surprises. When the sprint ends, you’re left with valuable work that is genuinely, completely finished.

Why a Definition of Done Is Non-Negotiable

Have you ever been part of a team where "done" meant something different to everyone? It's a classic project killer. Let's imagine a team, we'll call them Team Apollo. They were sharp and motivated, but every single sprint review was a mess of frustration. A developer would claim a user story was finished, only for a tester to immediately find a pile of bugs. Or the product owner would finally see a new feature and realize it was missing half of what they'd discussed.

This "done-but-not-really-done" cycle is incredibly common, and it’s where good projects go to die. When there's no shared agreement on what completion actually looks like, your team isn't just misaligned; they're speaking different languages. A developer’s “done” might mean the code is written. A tester’s “done” means it’s bug-free. The product owner’s “done” means it’s in the hands of users and delivering value. Without a clear standard, you're just setting yourself up for rework, missed deadlines, and a serious drop in morale.

The Power of a Single Source of Truth

This is where a solid agile definition of done changes the game. Think of it as a universal translator for your team. It’s not just another checklist to tick off; it's a formal agreement, a single source of truth that gets everyone on the same page, from the newest developer to the most senior stakeholder.

Once everyone agrees on what "done" truly looks like, that ambiguity that plagues so many teams simply evaporates. The impact is huge. In fact, adopting a shared Definition of Done in Agile has helped 97% of organizations worldwide achieve higher success rates. An incredible 98% of Agile adopters report better outcomes than they ever saw with old-school, traditional approaches.

This shared standard does more than just align people; it builds a culture of accountability. Team members don't have to guess or make assumptions about quality anymore. They have a clear, consistent bar to meet, which makes everything from sprint planning to long-term forecasting far more reliable.

Your Definition of Done is your team’s formal pact for quality. It transforms the abstract concept of "finished" into a concrete set of measurable criteria that everyone can stand behind.

Essential for Remote and Distributed Teams

For teams spread across different offices or time zones, a visible and respected DoD is even more crucial. When you're working remotely, you can't just lean over a desk or grab someone in the hallway to clarify a small detail. A formal DoD is what ensures a developer in Berlin and a tester in Bangalore are working toward the exact same outcome.

This creates the transparency and trust needed for people to work autonomously and with confidence. They know precisely what’s expected before a piece of work can be considered complete, which cuts down on the constant back-and-forth and micromanagement. A strong DoD is the bedrock for predictable delivery and high-quality work, no matter where your team members are. This level of clarity is also a key component in the bigger picture of agile release planning.

From Chaos to Predictability

Let's circle back to Team Apollo. Tired of the constant friction, they hit pause and decided to create their first Definition of Done. The whole team got together and hammered out a simple, clear checklist for every user story:

- Code is peer-reviewed by another developer.

- Unit tests are written and pass with 90% coverage.

- The feature is deployed to the staging environment.

- The product owner has reviewed and approved the functionality.

The effect was almost immediate. In the very next sprint, the number of bugs plummeted. The team's velocity, which had been all over the place, started to stabilize because "done" items were truly finished. But the biggest win? Trust was restored. The DoD wasn't just a document; it was their shared commitment to quality, and it completely transformed their workflow from chaotic to predictable.

DoD vs. Acceptance Criteria vs. Definition of Ready

In the world of Agile, it's easy to get tangled up in terms that sound alike but do very different jobs. Confusing the Definition of Done (DoD), Acceptance Criteria (AC), and Definition of Ready (DoR) is a common tripwire for teams, and it can lead to some serious process gaps and frustration. Nailing down what each one does is your key to creating a smooth, predictable workflow.

Let's use an analogy: building a custom car.

- The Definition of Ready is the pre-flight check before you even touch the engine. Do you have all the right parts, tools, and schematics?

- The Acceptance Criteria are the specific performance targets for that engine, like "accelerates from 0 to 60 in under four seconds."

- The Definition of Done is the final, universal inspection for the entire car before it leaves the factory. It covers everything from passing emissions tests to a flawless paint job.

Unpacking the Definition of Ready

The Definition of Ready (DoR) is basically the gatekeeper for your sprint. It’s a checklist, created by the team, that a user story has to pass before anyone can pull it into a sprint. The whole point of the DoR is to make sure the team has everything they need to start working without hitting immediate roadblocks.

A solid DoR prevents half-baked ideas from derailing a sprint. It’s the team’s way of saying, "We're not committing to this until it's properly defined and all the pieces are in place."

For instance, a DoR might require that:

- The user story is clearly written and everyone on the team gets it.

- All the necessary UX mockups and design assets are attached.

- Dependencies on other teams have been identified and discussed.

By sticking to a DoR, teams protect their focus and make sure that once work starts, it can flow. This upfront clarity pays huge dividends in efficiency and predictability down the road.

Defining Acceptance Criteria

While the DoR stands guard at the beginning of the process, Acceptance Criteria (AC) are unique to each user story. Think of them as a set of specific, testable conditions that have to be met to prove the story works exactly as intended from the user's perspective.

If the DoD is a universal quality checklist for all work, the AC is a custom-tailored test for one specific feature. This is where you get into the nitty-gritty of what a particular task needs to accomplish. You can see how AC fits into the bigger picture in our guide on writing a great user story template.

Acceptance Criteria answer the question, "How do we know this specific feature is complete and correct?" They are written from the end-user's point of view and are totally binary; each condition either passes or it fails.

For a new login feature, the Acceptance Criteria might look something like this:

- A user can successfully log in with a valid email and password.

- A user sees an error message if they enter an incorrect password.

- A user is redirected to their dashboard after a successful login.

Every user story gets its own set of AC to ensure its unique requirements are met.

How the Agile Definition of Done Is Different

Finally, we arrive at the agile Definition of Done (DoD). This is the big one, the all-encompassing quality standard that applies to every single piece of work your team produces. It's the final, universal checklist that certifies each item is truly finished and potentially ready to ship.

Unlike Acceptance Criteria, which change from one story to the next, the DoD stays consistent across all work. It’s less about what the feature does and more about the non-functional requirements and quality measures that guarantee consistency and technical excellence.

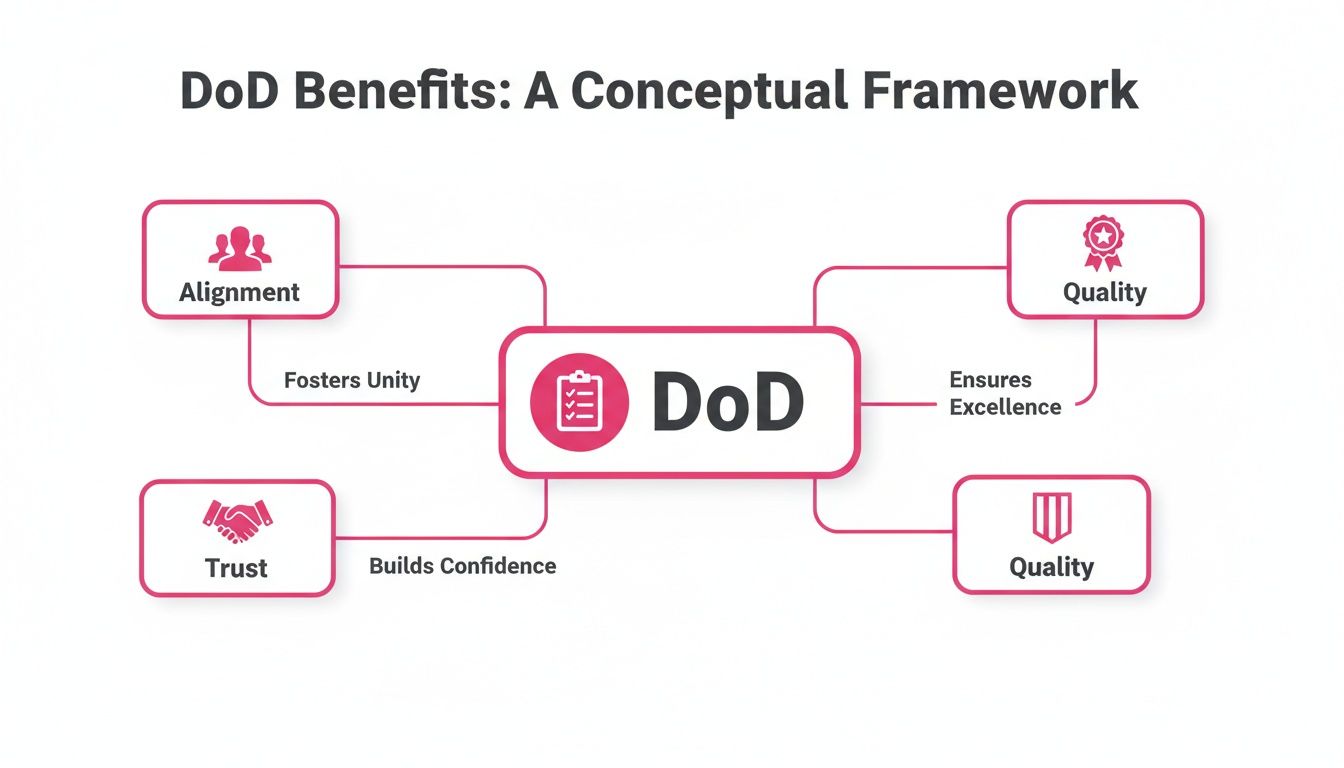

This is how a strong DoD supports core team benefits like alignment, trust, and quality.

As the diagram shows, a clear DoD is the bedrock for getting everyone on the same page, building trust through reliable delivery, and holding the line on quality.

The DoD is a major reason why Agile projects see 75% success rates, compared to just 56% for traditional waterfall methods. Teams with a strong DoD aren't just guessing; they see real results, with 42% reporting major quality improvements and 47% experiencing higher productivity.

A typical DoD for a software team might insist that:

- Code has been peer-reviewed by at least one other developer.

- Unit and integration tests are written and all are passing.

- The code achieves at least 85% test coverage.

- All relevant documentation has been updated.

- The feature has been successfully deployed to a staging environment.

When you put them all together, these three agreements (DoR, AC, and DoD) create a powerful framework. The DoR makes sure work is ready to start, the AC confirms a feature delivers on its specific promise, and the DoD guarantees everything the team produces meets a consistent, high-quality standard.

How to Create Your Team's Definition of Done

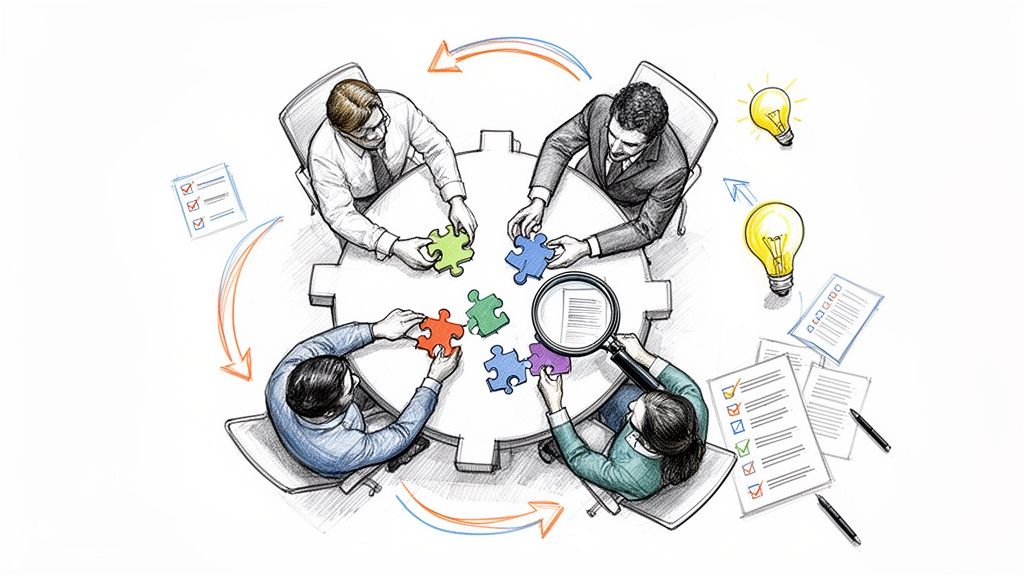

A truly effective Definition of Done isn't a mandate handed down from management. It's a pact, a shared understanding forged by the very people who will live by it every day. This is the secret sauce: when a team builds its own quality standard, they own it, they believe in it, and they'll fight to uphold it.

The best way to get there is by running a dedicated workshop. This isn't just another meeting on the calendar; it’s a focused, collaborative session where developers, testers, designers, and the product owner all have a seat at the table. The mission is simple: to collectively answer the question, “What does it really take for us to be confident our work is 100% complete?”

Step 1 Brainstorm Your Quality Standards

Kick things off with a blank canvas, a physical whiteboard or a digital one will do. This first phase is all about open brainstorming, getting every single idea about what "done" means out on the table. No judgments, no filtering.

Get the ball rolling with some probing questions:

- What's the first thing we do after the code is written?

- What makes us feel genuinely confident when we push a feature live?

- Think about past releases. What did we forget that came back to bite us?

- What are the non-negotiable steps to make sure our work is easy to maintain later?

You should end up with a big, messy list of ideas, which is perfect. You'll see everything from "peer reviewed" and "tests passed" to "docs updated" and "PO signed off."

Step 2 Organize and Categorize

Now it’s time to bring some order to the chaos. Look for common themes in your brainstormed list and start grouping related items into logical categories. This simple step makes the final DoD far easier to read and use as a quick-reference checklist.

For most software teams, you’ll find the categories naturally fall into buckets like:

- Code Quality: Anything related to the code itself, such as style, reviews, and best practices.

- Testing and Validation: All the activities that prove the work is solid and does what it's supposed to do.

- Documentation: Capturing and sharing knowledge so others (and your future self) aren't left in the dark.

- Deployment: The practical steps for getting the code out into the world.

- Approval: The final sign-offs that confirm the work meets business needs.

For instance, items like "code reviewed," "follows our style guide," and "no new linter warnings" all fit snugly under the Code Quality umbrella. You're transforming a jumble of sticky notes into a structured, actionable document.

A great Definition of Done is specific, measurable, and objective. Vague statements like "tested thoroughly" should be replaced with concrete items like "unit test coverage is above 85%."

Step 3 Phrase as Clear Checklist Items

With your categories set, the real work begins: turning each point into a crystal-clear, binary checklist item. Every single statement must be a simple yes-or-no question. There can be absolutely no gray area or room for debate.

This is where you sharpen vague ideas into concrete actions. For example:

- "Needs testing" becomes "Unit and integration tests are written and all are passing."

- "Docs" becomes "User documentation is updated in the knowledge base."

- "Someone else should look at it" becomes "Code has been peer-reviewed by at least one other developer."

This is the most critical step for making your DoD a practical tool instead of a theoretical document. When a developer looks at the list, they should know instantly if an item is complete. It's also vital to apply this clarity to other processes; for example, our bug report template shows how structure can eliminate ambiguity.

Step 4 Make It Visible and Adaptable

Your shiny new Definition of Done does no good buried in a Confluence page nobody ever visits. It has to be visible, every single day. Print it out and stick it on the wall next to your team board. Make it a permanent widget on your digital task board.

Constant visibility keeps quality at the forefront of everyone’s mind, acting as a gentle, persistent reminder of the promise the team made to itself.

Finally, treat your DoD as a living document. It’s not set in stone. As your team grows, your technology changes, and you learn from your mistakes, your definition of quality will evolve, too. Make a point to review it in your retrospectives. Ask, "Is our DoD still serving us well? What should we add, remove, or clarify?" This cycle of continuous improvement is what keeps the DoD a sharp and powerful tool for building great software.

Sample Definition of Done Checklist Template

To help you get started, here's a sample checklist. Don't just copy it; use it as a launchpad for your team's conversation and tailor it to fit your unique context.

| Category | Checklist Item | Example Metric/Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Code Quality | Code is peer-reviewed by at least one other developer. | Review completed in pull request. |

| Code adheres to the team's style guide. | Passes automated linter checks. | |

| Testing | Unit test coverage meets the team's standard. | > 85% coverage. |

| All acceptance criteria for the story are met. | Verified by the Product Owner. | |

| Passes all regression tests successfully. | No failures in the automated suite. | |

| Documentation | Technical documentation is updated. | Changes committed to the wiki. |

| User-facing guides are updated. | Knowledge base article is current. | |

| Deployment | Code is successfully merged into the main branch. | Merge is clean, no conflicts. |

| Deployed to the staging environment for review. | Feature is live on staging server. |

This template provides a solid foundation, covering the essential areas from code creation to final deployment. Let it guide your discussion, but always remember the most powerful DoD is the one your team builds together.

Common DoD Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Getting a Definition of Done on paper is a great first step, but the real magic happens when a team actually lives and breathes it over time. Even with the best intentions, teams can fall into a few common traps that turn a powerful tool for alignment into just another forgotten document.

Let's walk through these pitfalls. Knowing what they are is half the battle in keeping your DoD a living, essential part of how you build quality software.

The Overly Ambitious DoD

One of the most common mistakes is biting off more than you can chew. A team gets excited about raising their quality game and drafts this epic, aspirational checklist. It's filled with advanced practices they're not even doing yet, like 100% automated test coverage or hitting complex performance benchmarks.

This almost always backfires. When the standard is impossible to reach, people just start ignoring it. The DoD becomes a source of frustration, not a guide to success, and consistency goes right out the window.

How to Fix It: Start Simple and Iterate

The solution here is simple but effective: start with what you can realistically do right now. Your first DoD should be a mirror of your team's current abilities. It's far better to have a simple, five-point checklist that you hit 100% of the time than a twenty-point wish list that everyone ignores.

A practical, achievable Definition of Done that is consistently met builds momentum and trust. It creates a foundation of quality that the team can then strengthen over time through continuous improvement.

From that solid starting point, treat your DoD like a living thing. Your sprint retrospectives are the perfect place to ask a few key questions:

- Is our current DoD still working for us?

- Are we getting better? Is it time to raise the bar a little?

- What’s one small quality improvement we can add to our DoD for the next sprint?

This approach lets your quality standards evolve as your team matures. It keeps the DoD relevant, challenging, and motivating.

The "Set It and Forget It" DoD

Another classic blunder is letting the DoD become a relic. A team has a great workshop, writes it all down, and then files it away on a wiki page that no one ever visits again. As time goes on, tools change, processes get updated, and team members come and go, but the DoD stays frozen in time, becoming more and more irrelevant.

How to Fix It: Keep It Visible and Alive

To stop this from happening, you have to make your DoD impossible to ignore. Print it out and stick it on the wall next to your task board. If your board is digital, put it right at the top.

Even more importantly, make it a regular topic of conversation. The sprint retrospective is the ideal time to pull it up and ask, "How are we doing with this?" This simple ritual turns the DoD from a one-time task into an active, ongoing agreement that reflects the team's commitment to excellence.

The "We're Under Pressure" DoD

This is probably the toughest challenge of all: sticking to your DoD when a deadline is breathing down your neck. It’s so tempting to cut corners when you’re under pressure, maybe skipping a peer review here or putting off updating the documentation there. But that's a slippery slope that leads directly to technical debt and poor quality.

How to Fix It: Hold the Line

The fix here comes down to two things: discipline and empowerment. The team, with the Scrum Master leading the charge, has to treat the DoD as a non-negotiable quality gate. It’s a collective agreement: if a story doesn’t tick every single box, it’s not done. Period.

This takes courage. It means being prepared to tell a Product Owner or stakeholder that a feature isn't shipping this sprint because it didn't meet your shared quality standard. By holding the line, the team sends a powerful message that a sustainable pace and high quality are more important than pushing incomplete work across the finish line.

Frequently Asked Questions About the DoD

Getting the hang of the Definition of Done is one thing, but putting it into practice often brings up some tricky questions. Teams new to the concept often wrestle with who owns it, how broad it should be, and how to keep it relevant. Let's tackle some of the most common questions that pop up on the ground.

Who Is Responsible for Writing the Definition of Done?

The short answer? The entire development team.

While a Scrum Master might get the conversation started and the Product Owner will definitely have input on what "quality" means for the business, the people doing the work are the ones who have to build and own the DoD. This collaborative ownership is the secret sauce.

When a DoD is handed down from on high, it rarely sticks. It just feels like another checklist to begrudgingly follow. But when the developers, testers, and designers who live in the code every day hash it out and agree on their own quality bar, they become genuinely invested in hitting it. It’s no longer just a document; it becomes the team's shared commitment to excellence.

Can a Project Have More Than One Definition of Done?

Absolutely. In fact, it’s a smart practice to have multiple, layered Definitions of Done. Think of it less as a single document and more like a series of quality gates, with each one getting progressively tougher as you get closer to shipping.

Here’s how a team might layer them:

- For a User Story: This is your baseline. It covers the fundamentals, like code being written, peer-reviewed, and passing all its unit tests.

- For a Sprint: This level builds on the story. It might demand that all stories from the sprint are integrated, the build is stable, and everything passes regression testing.

- For a Release: This is the final boss. It's the ultimate checklist to ensure the product is truly ready for customers. This could include things like passing performance and security scans, getting final stakeholder sign-off, and having all user documentation ready to go.

Each DoD builds on the one before it, creating a clear and reliable path to a high-quality product. This structure ensures you’re not just completing tasks, but consistently building something solid and shippable.

How Often Should the Definition of Done Be Updated?

Your Definition of Done should never be a static artifact collecting digital dust. It’s a living document that needs to evolve right alongside your team, their skills, and your tech stack. The perfect place to give it a check-up is during your Sprint Retrospective.

That’s when the team is already reflecting on what worked and what didn't, making it the ideal time to ask some honest questions about your quality standards.

- Is our current DoD still working for us?

- Have we learned a new skill or adopted a new tool that lets us raise the bar?

- Did something slip through the cracks last sprint that our DoD should now prevent?

A good rule of thumb is to formally review it every few sprints, or anytime something major changes, like a new team member joining or adopting a new piece of technology. This keeps your DoD sharp, relevant, and genuinely useful.

What Happens If Work Fails to Meet the DoD?

This is where the rubber meets the road, and team discipline is everything. If a backlog item doesn't check every single box on the Definition of Done by the end of the sprint, it is not done. Period. There’s no such thing as "99% done."

In that situation, the work doesn't get demoed in the Sprint Review because it’s not a finished piece of value. It also means it doesn't count toward the team's velocity for that sprint. The unfinished item goes right back into the Product Backlog, and the Product Owner will decide when to schedule it again.

This might sound harsh, but it's a core tenet of Agile. This strict rule prevents the slow, painful buildup of technical debt from half-finished work. It’s how teams build trust with stakeholders and maintain a sustainable pace without cutting corners.

Stop losing track of your hard work and achievements. With WeekBlast, you can log your wins in seconds, creating a searchable, permanent record of your progress. Replace status meetings and chaotic updates with a simple, human-first changelog that gives you and your team total visibility. Start your free trial of WeekBlast today.